Yearbook 2008

Burma. The isolated and internationally defended military junta was preparing a controversial referendum on a new constitution when the southern parts of the country suffered a severe cyclone in early May. According to the UN’s latest estimates, around 130,000 people were killed and around 2.4 million lost their homes or suffered severe distress of another kind. Nevertheless, it took a few weeks for foreign aid to a considerable extent to be allowed into the country. Not until after two weeks did the junta general General Than Shwe visit the disaster area. At the end of the month, at the end of the month, the junta agreed to admit all foreign aid after a meeting between Than Shwe and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon. See sunglasseswill.com for Myanmar travel guide.

The military junta requested the equivalent of $ 11 billion in aid from the outside world. The UN and ASEAN estimated the cost of reconstruction to be over a billion dollars, and at an international donor meeting, pledges of just under $ 50 million were made.

- ABBREVIATIONFINDER: Click to see the meanings of 2-letter acronym and abbreviation of BM in general and in geography as Myanmar in particular.

While the devastation in the cyclone area was most acute, the planned referendum in the rest of the country was carried out. Officially, 99 percent of voters were said to have participated, and 92.4 percent of them said yes to the Constitution guaranteeing the military a quarter of seats in parliament and the last word in all political decisions, as well as the head of state being military. The opposition party National Democracy Federation (NLD) dismissed the vote as a major fraud and claimed that in many places there were soldiers filling in the ballots.

After the referendum, political repression was sharpened. UN envoy Ibrahim Gambari visited Burma twice during the year but was not allowed to meet either the junta leader or opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi. The latter had several meetings with a junior representative but no progress was reported.

In September, Win Tin, one of the leading democracy activists, was released after 19 years in prison. In October, one of Aung San Suu Kyi’s closest confidants, Ohn Kyaing, was arrested without explanation. He had already been in prison for 15 years for spreading regime-critical leaflets.

Over a couple of weeks in November, more than 100 democracy activists were sentenced to long prison sentences. Ashin Gambira, leader of the monks’ protest movement in 2007, was sentenced to 68 years. Several of those who led the protests against the 1988 junta were jailed for 65 years. Popular comedian Zarganar was sentenced to 45 years in prison for regime criticism. Blogger Nay Phone Latt got 20 years to write about the tough life in Burma.

Warriors of the minority people

Unresolved ethnic conflicts in Myanmar have given rise to many and long wars. At the liberation of the colonial empire in 1948, minority people demanded a high degree of self-reliance, but did not get it. Nor was account taken of the already established autonomy and old customary law. Throughout the nation’s history, the states in the border areas have been haunted by civil war and ethnic strife. Liberation movements in various constellations have led the armed struggle for self-government, which has contributed to Myanmar’s complicated geographical, demographic and political structure.

A persistent problem after independence has been the conflicts between the central government and various rebel movements among ethnic minorities. After the 1962 coup, the regime attempted to make peace with the rebel armies, but failed. The conflicts continued until the 1990s. After 1988, the junta carried out a strong military armament that in a few years doubled the army’s strength.

Following military offensive, several ceasefire agreements were signed between the military and a number of rebel groups in the early 1990s. This opened up an opportunity for the military and intensify the fight against Karen people’s guerrilla army during the Karen National Union (KNU). In 1995, the karen-guerrilla’s main base, Manerplaw, fell. In the period 1990–1995, Manerplaw was also the “capital” for a counter-government formed by the country’s democratic opposition. It was led by Sein Win, cousin of Aung San Suu Kyi. After the defeat, a more sporadic guerrilla from KNU continued, and the chin and shan minorities also continued the fight.

In 2006, the military launched a new offensive against self-reliant minority people, primarily the resistance army’s army. At least six ethnically based militia groups clashed with the government in 2006-2007. In the 1990s, a number of ceasefire agreements of varying scope and durability were signed. For many of the minorities, the struggle for self-rule has been just as much a defense war against the army’s extensive abuse.

New capital

In the fall of 2005, the junta quickly started moving the country’s administrative capital from Yangon to a newly developed city named Naypyidaw. Only afterwards did diplomats and international organizations learn about the surprising relocation. The construction work was kept secret for several years, and was still ongoing. However, government offices, parliament building, airport and other infrastructure were completed.

Naypyidaw was officially inaugurated as a capital in May 2006 with a military parade in which 12,000 soldiers participated. At the same time, a wage increase of 400-500 percent was announced for the country’s low-paid civil servants. The officer stand was given even greater mark-ups. This had a clear inflationary effect, along with huge construction costs for the new capital.

Population 2008

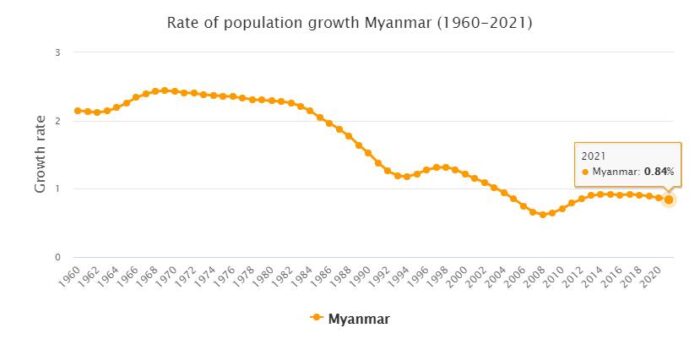

According to Countryaah reports, the population of Myanmar in 2008 was 50,600,707, ranking number 25 in the world. The population growth rate was 0.670% yearly, and the population density was 77.4554 people per km2.